Text and Drawings by Abraham Storer

Although it’s still early in the season, Fiona Mulligan’s Eastham garden is full of green, and her small hillside orchard is dotted with flowering saplings. She usually starts her gardening in late February after doing some winter traveling.

Originally from New Jersey, Mulligan spent years traveling the world before moving to the Cape a decade ago. She has farmed in India, Peru, and Ecuador. “My traveling never had anything to do with tourist destinations,” she says. “It was how do I get to a village in India and learn how they grow food?”

She has since crafted her own approach to working with the soil, guided by a commitment to regenerative agriculture, intended to leave the soil better than one found it without much input.

Here, Mulligan has two interdependent occupations: she creates gardens with her Woven Seeds Edible Landscapes, and she uses much of what she grows in her own garden in products she creates for her side venture, Healing Hands Herbs.

Q: What’s an edible landscape?

You can design a landscape with all (or mostly) edible plants and have it still look like a landscape. There’s a replacement for almost every well-known nursery plant you might want that will also give you food, feed the birds, and help with pollinators. For example, a peach tree could be in place of any tree you put in your yard.

Q: How do you prepare the soil in your garden?

Q: How do you prepare the soil in your garden?

I follow a no-till, regenerative system. In my garden there’s a soil area where I grow food and then a walkway area that’s dug into a swale, which is like a ditch that I fill with wood chips. The soil is super fluffy because I’m very strict about never walking on it. I add a little layer of compost and just leave it, and that’s it.

Any kind of tilling with machinery creates compaction — a thing called the dead-pan layer underneath the soil. Weeds love compacted soil. Plants struggle to get through that dead-pan layer and then when it rains that top fluffy layer is much more likely to erode off.

Q: Do you use any pesticides?

I don’t use any spray, even organic ones. I try to grow flowers that I know attract ladybugs that kill aphids and soft-body caterpillars. Ladybugs love sweet alyssum. Dill and cilantro, both umbel plants, attract parasitoid wasps that we love. They go after a lot of soft-body caterpillars that would eat my plants.

Q: What about fertilizers?

There’s comfrey up there that is permanent and always here — it’s an herb that has multiple uses. It’s really healing for the skin, so it gets infused into a lot of my healing products. But I also chop it up, mix that with fish and seaweed, and make fermented liquid fertilizers.

I then put the fermented mixture into my fertilizer injector that’s attached to my spigot and hooked up to my drip irrigation, so it drips watered-down fertilizer that constantly feeds the soil. It’s kind of like the benefit of eating fermented food.

It smells bad. Terrible.

Q: Tell me about how you grow figs in this climate?

They’re a cold-hardy variety, and if you cover them they will last through the winter. They’re still hot weather plants, so they like it hot and dry.

I cover them before the first frost. I use straw and burlap or cuttings from our grass. Basically, you make a mound that covers the fig sapling by at least a couple of inches. You want to keep it all down with some burlap and stakes. It keeps the temperature a little more stable when they are dormant. I uncovered my fig trees in mid-April.

Figs are easy to propagate. When they’re dormant, you have to prune them anyway. I like to prune them to fit them into the protection that I’m going to put around them for winter. So, when I prune, I put a bunch of cuttings into the soil and see what takes.

Q: Do you fertilize the trees?

For big plantings, I don’t amend the soil too much. I plant them and put a heavy dose of wood chips on them. That breaks down over time and feeds the plant. You can see how much richer the soil is compared to the sandy soil originally here.

Q: What’s something growing in your garden right now that you discovered while traveling?

Q: What’s something growing in your garden right now that you discovered while traveling?

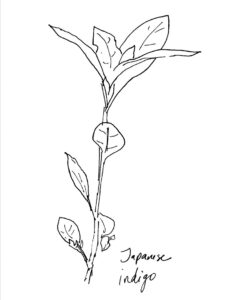

The Japanese indigo I learned about from a permaculture farm in South India. I have Irish sea kale that I learned about in Ireland. This is what my ancestors ate. It’s a perennial kale that grows wild all over the northern coast of Ireland and Scotland. In the garden, it spreads rapidly every year. It’s hardier than the kale we normally grow. I also have a Portuguese sea kale that I learned about there.

Q: Do you often experiment in your garden?

When you’re really into plants, experimentation just kind of snowballs. Last year I got into taking flowers from my garden and pressing them against shirts and bundling them up and boiling them so that the flower imprinted itself onto the fabric.

Right now, I’m really excited about Japanese indigo. I’ll probably dry it and make some kind of salve because it is good for skin, but I’m mostly growing it for dye. I’ve been on a kick for botanical dyes lately. Indigo has a long, complicated history. Rather than making money from it, I’ll use it to dye socks and shirts and maybe make some gifts.

I feel like my whole life has just been playing in a garden. It’s all I’ve really thought about and cared about for the last 17 years.