Far from the heroic scale and subject matter of works by many of his contemporaries, Will Barnet’s flat, crisp compositions often depicted women (and their cats) in domestic spaces. Born in Beverly and educated at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Barnet lived most of his life in New York, where he built a successful career as a painter, printmaker, and influential teacher. At age 100, he was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the National Academy Museum in New York and was awarded the National Medal of the Arts by President Barack Obama. Barnet died at 101 in 2012.

In 1956, Barnet spent a summer in Provincetown that influenced his approach to merging his experiences with the concerns of abstract painting. The current exhibition of Barnet’s prints at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum charts his development as an artist and conveys his range through both his signature mature work and lesser-known earlier work. All of the works in the show are part of a collection donated to PAAM by Jack Krumholz and Marjorie Jacoby in 2022.

The exhibition is introduced by a text quoting a statement Barnet wrote in 2009. “I remember walking down a road [in Provincetown] and feeling very happy to be in an environment surrounded by sun, water, and sailboats,” he wrote. “These feelings had a great impact on my palette and I created a series of works, which had various levels of nature: under water, above the water and in the heavens … In a sense, I found compartments, colors, changes equivalent to the experiences I had in nature.” This ability to find inspiration in nature and translate it into something “equivalent” remained important to Barnet throughout his career. Feelings like the joy of walking by the water became a central concern in his work, even if his images evolved more toward abstraction and away from direct depiction of reality.

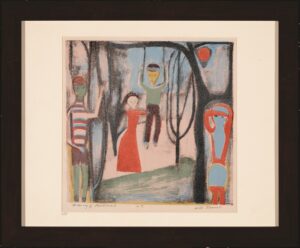

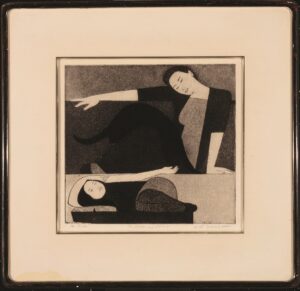

Although none of the work Barnet made in Provincetown is included in the current PAAM show, a picture from this period titled Guinea Hens reflects this approach. Despite its title, there are no identifiable animals in it. Rather, Barnet creates a Cubist composition with textures that evoke feathers and angular shapes suggesting the fowls’ prickly and restless energy. Other pictures from the 1940s and ’50s show Barnet’s interest in primitive forms, particularly a group of three scenes of childhood — Go-Go, Memory of Childhood, and Child Among Thorns — rendered with the flattened space, rough shapes, and direct line work characteristic of art made by children. In Barnet’s later work, the clean shapes and precise division of space echo the elegance of his recumbent female figures. Both examples show how form and subject are inseparable in Barnet’s art.

Although Barnet’s imagery seemed to become more realistic as he developed as an artist, a print from 1987, Big Grey, is one of the most abstract pieces in the exhibition. It demonstrates how the show’s narrative is more complicated than telling the story of how an artist moved from abstraction toward realism. In Barnet’s work, shapes become symbols that are imbued with meaning and feeling; while they are rooted in experiences of reality, they blur traditional modes of representation. Barnet showed an openness to pull from both realist and abstract approaches to artmaking, a range that was shared by other artists in his orbit: he studied at the Art Students League of New York with Stuart Davis, who was known for his Cubist-inflected cityscapes, and Charles Locke, a figurative draftsman. The PAAM show credits Barnet with influencing a later generation of artists, including James Rosenquist and Cy Twombly.

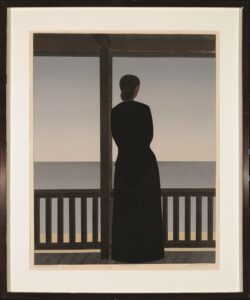

Woman by the Sea is the most striking piece in the show, and one that best represents Barnet’s formal and emotional brilliance. The print depicts two spaces: a dark and rectilinear porch, and an expanse of gray sea below a sky stained with the colors of dusk. In an allusion to Romantic imagery, a woman in silhouette stands on the porch looking out at the sea. The dark lines of the fence and the boxlike construction of the space confine the figure in a sort of cage. She is imbued with deep longing while the sea and sky beckon with their openness and light. The dense rhythm of the porch fence is balanced by the open expanse of sea and sky, just as the curves of the woman’s body are balanced by the angular lines of the architecture surrounding her.

Along with the quiet harmony of the muted colors, the balances create a feeling of calm and comfort. Barnet evokes the meditative experience of looking out at the sea not just through imagery but also through form. This achievement is what distinguishes the picture as art and not just another scenic image of the sea. “The inspired, independent artist searches for meaning that lies hidden beneath things seen and felt,” he wrote. “His vision is to find concrete shapes that express and communicate his feelings and to state them in fresh vital terms.”

The strongest shape in the painting is the silhouette of the woman, which becomes a repository of melancholic feeling: a dark void at the center of the picture, as shrouded and contained as the woman’s buttoned-up and restrictive clothing. The shape is precisely rendered in its details — the tilt of the head, the angle of the shoulder — yet is still abstract and flat. The tension is much like emotion itself: something located in circumstances of the external world that remains inherently internal and abstract.

Barnet said his inspiration for Woman by the Sea came from catching a glimpse of his wife standing on a porch in Maine at twilight. It struck him as a moment to remember: “I made a sketch of the scene and began a series of paintings of women and the sea,” he wrote.

Moments like these grounded his work regardless of the form it took. “My work is constantly revitalized by direct contact with reality,” he wrote. “The abstract work is never concerned with amorphic feeling but always with visual images of very real experiences, which demand that each form exist in its own sharply defined character.”

Imagery and Form

The event: Prints by Will Barnet from the museum’s permanent collection

The time: Through May 29

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 general admission; see paam.org for information