When artist Susan Baker showed her work at the Fine Arts Work Center in 1974, Mary Hackett, then in her late 60s, attended the opening. The next day, Baker visited the gallery and found Hackett making a painting of the exhibition space. This odd and delightful situation was the start of a friendship among Hackett, Baker, and Baker’s husband, Keith Althaus, which lasted until Hackett’s death in 1989. The painting that Hackett made now hangs in Althaus and Baker’s North Truro home.

“Her quirkiness was her charm,” says Baker. “She would do unexpected things.”

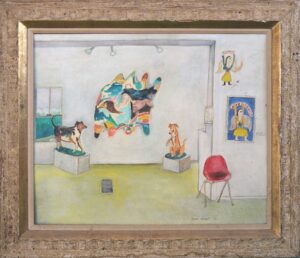

Hackett’s painting of Baker’s show is similarly eccentric. The gallery is described in exacting if imperfect detail, down to the lighting fixtures and an air vent on the floor. Its white austerity is interrupted by colorful works of art. Hackett employs basic drawing techniques and minimal shading to suggest spatial depth, but it’s unconvincing: the rear legs of a chair don’t exist on the same plane, and the space of the gallery feels too shallow to allow visitors to walk among the sculptures. The overall effect is a flattened space that exists in limbo between something imagined and something keenly observed.

“She had the confidence to use empty space in bold and quirky ways,” wrote Althaus in a catalog essay accompanying a 1996 retrospective at the Cape Museum of Fine Arts (now the Cape Cod Museum of Art). “Sometimes the space is disconcerting and unsettling … she did not ‘doctor’ the paintings to make them more readable or familiar.”

Hackett taught herself to draw in her early 20s and began painting a few years later. Her work has an unselfconscious frankness typically associated with self-taught artists and is distinctive for its detailed depiction of what was around her — both in Provincetown, where she lived most of her life, and in the wider world, where she traveled frequently. Just about everything interested her: the view outside her window, a television broadcasting a soap opera, a broken baby chair, an untidy kitchen.

“She painted what was around her,” says artist Helen Miranda Wilson, whose father, the literary critic Edmund Wilson, was friendly with Hackett. She recalls Hackett vividly: “She had long auburn hair and little blue eyes and very white skin.”

Hackett married Chauncey Hackett, a prominent Washington, D.C. lawyer, in 1926. The couple moved to Provincetown in the 1930s and became fixtures in the bohemian cultural scene. “There was a lot of drinking, and at a certain point Bubs got religion,” says Wilson, referring to Hackett by her nickname. “She went very Catholic, but not in a bad way.”

Althaus remembers a shrine in Hackett’s bedroom where she would pray. “The religious thing maybe held everything together,” he says. Some of her artwork incorporated religious themes, including a series based on Francis Thompson’s popular 19th-century poem “The Hound of Heaven.” Althaus points to one painting in his collection where the “hound” of the poem is represented by a pair of boots pursuing a figure on a donkey: “The poem is about how you can’t run away from Christ,” he says.

Her faith would sustain her until the end. “She went into a nursing home at the end of her life,” says Baker. “She called me and said, ‘I’m dying, and I want to talk to you before I die.’ I burst into tears, and she got really angry at me because she thought she was going to a better place.”

Hackett has long been revered by other artists, both during her lifetime and after. Provincetown’s Jay Critchley and John Dowd are devoted admirers. Baker and Althaus say that John Waters wanted to buy a painting of a Christmas tree that they own and another piece in their collection — a double-sided work with a hand surrounded by smoke on one side and an image of two keys on the other — was a favorite of Edward Gorey.

But Hackett maintained a distance from the established art world. “She didn’t have the sense that she was in a class of professional artists,” says Althaus. He contrasts her approach with that of the more conventional artists in her milieu: “She differs greatly from the studio painters who experiment every day in hope of discovering something which will stimulate them further,” he wrote. “As very often with the visionary artist, the painting is already realized before she starts to paint, and the task is to faithfully execute it.”

In a 1983 interview with Jay Critchley on WOMR radio, Hackett offered perspective on her practice. “I didn’t take myself seriously,” she said. “I just thought it was fun.” She contrasted herself with her friend John Dos Passos: “I asked him whether he got any pleasure out of his writing, and he looked at me askance, and he said, ‘Pleasure! I’ve long since gotten out of the amateur stage.’ So, you don’t have pleasure unless you’re an amateur? I got the message.”

Althaus notes that Dos Passos’s response was typical of the male artists of her time. “They were often ruthless in their efforts to divest themselves of obligations except those of their art,” he says. “The artist who is a wife and mother is rarely able to be so free. Mary Hackett certainly tried, but the domesticity of much of her subject matter — its closeness to home — shows how hard it was to escape these ties.”

While Hackett’s work began to receive more serious attention in her last decades, Wilson bristles at the idea that she was “discovered” late in life or after her death. “Everyone around here knew she made paintings,” says Wilson. “She was never discovered here — she was known.” Wilson also credits Hackett for her devotion to artistic freedom. “An artist wants to do things with their hands and make things to look at,” she says. “You do it no matter what else you’re doing. Hackett did it all the time, whether she got recognition or not. She wasn’t a careerist. Her trajectory was never to get a gallery to represent her.”

Still, Baker notes that Hackett was sensitive to criticism. “I think she thought her work was great, which was why it hurt her that people didn’t value it,” says Baker. “She liked it when people really raved about the work.”

“She is a great painter,” says Althaus. “Some people think her work is nothing. Some people overvalue it. She had a sense of both sides of the argument.”

A sense of contradiction feels central to Hackett’s life and work. As an artist, she was both celebrated and dismissed. She was self-taught but didn’t have the disadvantaged or rural background common to other self-taught artists. She valued her work but didn’t take it too seriously. (She apparently never liked to see her work in gold frames: “You’d give her a ratty old frame and she’d be ecstatic,” says Baker.) She enjoyed vacationing in Europe and New Bedford equally and moved between religious and secular circles throughout her life.

She also changed her mind frequently. On the back of a painting dated 1973, she wrote, “Annoyed with new changes in church, especially the handshaking bit” — but updated her opinion in another note dated 1987: “I changed my mind and am no longer annoyed.” She was aware of her own evolving view of Provincetown in her WOMR interview: “In the last 20 years or so when it got so terribly overcrowded, I began to hate it, but I changed my attitude — all of a sudden, I thought, this is a great place! You don’t have to go to a show — there’s a whole show going on right in front of you.”

On a wall in Althaus and Baker’s living room, Hackett’s painting of a Christmas tree hangs among works by Baker. In the painting, the scene outside the window — a palm tree and a building — is just as important as the interior view. A light cord is painted with as much care as Hackett’s beloved dog, which lies on a couch that seems to float off the floor. There is no hierarchy among elements. Everything seems of equal interest and value. It’s a testament to Hackett’s enduring openness and curiosity about the world around her.