A sou’easter blew the tide into Provincetown in December. Then, this past Saturday, a piece of the polar vortex swept by, stunningly cold. These strange storms have me remembering our more usual rhythms, ready for what an old-timer might call “a proper storm.”

I was living in a house on the Truro-Wellfleet line on the northern bank of Herring Pond in the winter of 2013 when that year’s big nor’easter came through.

The house is one of big windows, nestled gently into its surroundings — a place where all the movements of the pond and the woods and the natural world feel a part of the home. We were a week into February when the storm first appeared in radio warnings and as little red marks on weather maps. As it neared, the warnings this would be a proper storm were more insistent. It would be a nor’easter. And as its anticipated size grew bigger, so did my excitement: I love a good storm. I filled the bathtub with water, rounded up candles and batteries, and brought in enough firewood to last three days.

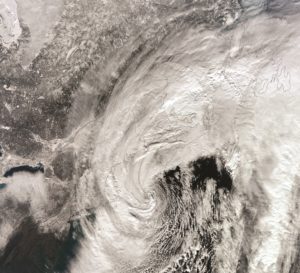

Our nor’easters are particular to this place. Most are born in the latitudes to the south, between Georgia and New Jersey, forming within a narrow corridor along the coast. They begin when warm, humid air over the Gulf Stream and cold dry air moving southeast from the arctic by way of Canada jostle for equilibrium. They build as they advance northward, becoming engines of their own increasing agitation. They tend to move offshore just south and east of Cape Cod. When that happens, we find ourselves directly in the path of a hundreds-of-miles-wide fetch of wind blasting in from the open ocean. Nor’easters are massive, formative forces that shape the landscape. I think of them as part of the personality of this place.

That night brought a glorious and powerful nor’easter. With it came heavy, wet snow that filled the forest thigh deep. Flake by tiny flake, a massive weight settled into the canopies of the tall pines. And then the wind began to move. Gusts came swooping in off the ocean, over the dunes, and across the ponds. This wind had traveled for hundreds of miles along the open ocean. The first thing it encountered that resisted its force were the laden pines, top heavy with snow, standing on the southern banks of the pond. The wind hit them with such power that they twisted and snapped. They were not uprooted; their roots held strong in the soil. But 20 feet up, their trunks spun and tore.

I attempted sleep, but the animal awareness inside me was tuned to the energy and movement outside. My sleep was shallow and shot through with waking. All through the night I heard the sharp cracking of trunks as the trees broke and fell. In the morning, the world looked different than it had the day before. The trees were laid out in swaths; each gust of wind was made visible by the alley of destruction it cleared.

It took a day’s work with a chainsaw and a four-wheel-drive truck before I reached the paved road, which I followed directly to the ocean — the only thing to do on the day after a nor’easter. After the wind has passed, the storm remains there, waiting to be witnessed.

The relationship between the wind and the ocean is an intimate one. Recruited by the tons of sky pressing down and moving over its surface, the ocean comes alive in the presence of a storm. Water is a medium of movement and a carrier of energy. And when the energy of a storm has been brought to it, the ocean banks its fury.

In a nor’easter, waves travel over vast distances, gathering power as they run unhindered towards the little sliver of sand that is the Cape. They gnash at the beach and dunes, eating tons of sand, so that in a single night, the beach is transformed.

Through my windshield, shattered by a falling branch, I look for the changes. A deep sand drift occupies the parking lot a hundred feet back from the edge of the dune. The concrete bathroom structure is encased in ice, frozen salt foam, and sand. Below, the waves charge like white horses, manes wild in the wind, toward the dunes they have been devouring all night. What the day before was even, settled beach, is now a sharp cliff running parallel to the sea. Slabs of dune are swept away to become next summer’s sandbar.

The storm has destroyed things I believed permanent. But I see for myself it is also creative in the change it has brought. A nor’easter is not something that happens to this place. It is of this place — as much a part of the landscape as the dunes, the sea, the marshes, and the tide.