A fickle system determines which artists are remembered and which are forgotten. The Outer Cape has its canon of artists. Some are known internationally, like Edward Hopper, while others are remembered more locally. But some have fallen off the radar.

Charles Heinz was active in Provincetown from the late 1920s until his death in 1953. Although unassuming, he built a solid reputation for himself.

“There are few like him in use of bold color, bold style and bold handling, and each year he seems to get more bold in all three,” wrote George Yater, director of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, in 1948. But today, Heinz’s works rarely sell for over $1,000. “He’s not a name 80 percent of our clients know,” says Spencer Keasey, director of Provincetown’s Bakker Gallery and Auctions. He is “just another forgotten artist,” says PAAM archivist James Zimmerman.

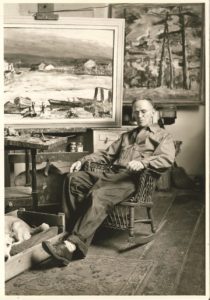

Yater photographed Heinz in a rocking chair at his 17 Race Road studio. Heinz doesn’t meet the photographer’s gaze. He looks down, his expression melancholic. His dog lies in a wooden crate at his feet.

The Provincetown Advocate profiled him in 1948, noting Heinz’s “eleven-year-old dog, Buster, a native like himself of Illinois.” Heinz’s reserve is emphasized to the point of caricature in the article, which begins by comparing the artist to a “drab, worn” book cover and continues, “The day of the visit was a Cape Cod fog gray, a background into which the artist merged easily and without protest. His house standing gaunt on the ragged outskirts of the town is like his studio, unadorned. There was nothing on his easel and as far as could be ascertained, less on his mind.”

Other contemporaneous accounts described his quiet demeanor. “One cannot talk for a moment with Charles Heinz without realizing that he is different,” reported the Shelbyville Union — Heinz’s hometown newspaper in Illinois —in a more sympathetic 1936 feature. “There is a shy, direct simplicity about the man, which invites your closest attention.”

During this period, Heinz was employed in Provincetown by the Works Progress Administration, which itself described him as “inarticulate in speech, slow, and self-effacing.”

Most descriptions of him highlight the contrast between the artist’s personality and his artwork, which is characterized by vivid color, energetic — even brutal — gestures, and a confident disregard for finish.

“Could this be the artist who grabs a handful of hot sunlight and lays it on his canvas!” asked the Advocate. “Who can reach into hell for reds that burn and glow! Whose skies can combine the anger of all tempests and seas the sullen power of quiet fury!”

Heinz took a more modest view of his art. “I always did like to draw,” he told the Shelbyville Union. “I never went to school after the eighth grade, but I’ve read a lot.” He studied at the St. Louis School of Fine Art and the Chicago Academy of Fine Art, but afterward he returned to his hometown, first as a sign painter (“Judging from the huge sign near his front door bearing the single name Heinz, he couldn’t have been too good,” wrote the Advocate) and then as a farmer. “There was 10 or 12 years that I took to farmin’ because I couldn’t make a livin’ at paintin’,” Heinz said.

Heinz came to Provincetown in his 40s to study with Richard E. Miller. By 1936, he had exhibited work at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. He showed regularly at PAAM, where he was a trustee, was an active member of the Beachcombers, and wrote a letter to Anton “Napi” Van Dereck in which he asked for help placing his work in newspapers.

“Heinz has something to say but he digs it out of his soul with a shovel,” wrote Orleans artist Vernon Smith in a WPA assessment of Heinz in 1936. “I think more of this painter’s work than they do in the office.” A year later, Smith’s WPA colleagues seem to have come around to agree with him. One wrote that Heinz “has justified everything Vernon Smith said about his works,” and noted that the New York Times chose one of his paintings for an article about a show of Provincetown artists.

But even Smith still had reservations, writing that Heinz “should go back to the farm in Illinois and paint the scenes he knows so well. He should get away from Provincetown influences which confine him and work it out alone.”

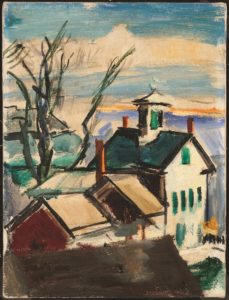

A small painting in the PAAM collection, The Grozier (Cabral) House, shows Heinz grappling with a motif common to Provincetown artists of that era: New England homes leading to the harbor, their roofs a jumble of flat planes. The architectural elements do seem to confine the artist, but just barely. He renders a brown roof in the foreground with a brusque gesture, the edges of the shape raw and tattered. The plane of a building in the middle ground is described with a single gestural mark. A bare tree breaks from its rigid environs, its scraggly branches reaching upward to a sky described with hurried strokes of blue paint that only partially cover the raw and stained canvas.

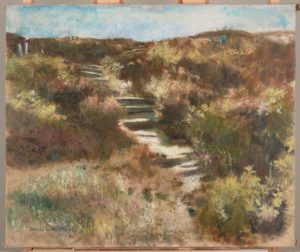

Heinz’s Wellfleet Vista, on view at the Seamen’s Bank branch there, is even more wild in execution. He indeed seems to empty his soul onto the canvas through the smeared, sooty grays of the sky.

Heinz painted in Wellfleet with increasing frequency toward the end of his life, when he upgraded his mobile studio from a delivery wagon tied to a bicycle to a jeep. Although he never made it back to the farm in Illinois, Wellfleet seemed to provide him with subjects more untamed than those he could find in Provincetown. There’s a synchronism between his style, roughly hewn and provisional, and some of his Wellfleet subjects, like decrepit oyster shacks.

Although he lived alone, Heinz apparently remained close with his family in Illinois, often visiting in winter. He died there at age 67 while visiting his sister.

Heinz never achieved the fame of some of his peers in part because his work was outside the norm. Whereas many of his contemporaries were influenced by movements of the time, including Realism, American Modernism, and Cubism, Heinz carved out his own path. His work appears more connected to the bright colors and hurried gestures of Fauvism and Expressionism — movements not typically associated with the Provincetown School. As the Advocate wrote, “He knows of but one place to put his color, his spirit, his life — on canvas.” That sentiment was central to the Expressionist ethos.

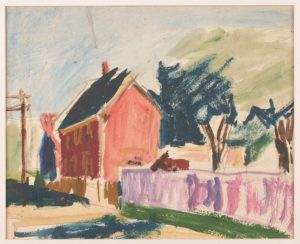

Heinz’s Red House, Conwell Street speaks to this boldness and direct expression. The blue tree and purple fence show an expressive use of color, and his depiction of light is evidence of careful observation. His gestures, agitated and improvisational, describe things as they are, but also move toward abstraction. Heinz died when Abstract Expressionism was exploding across the American art scene. Red House, Conwell Street points toward that future — and reflects a gutsy vision that is singular in the history of Provincetown art.