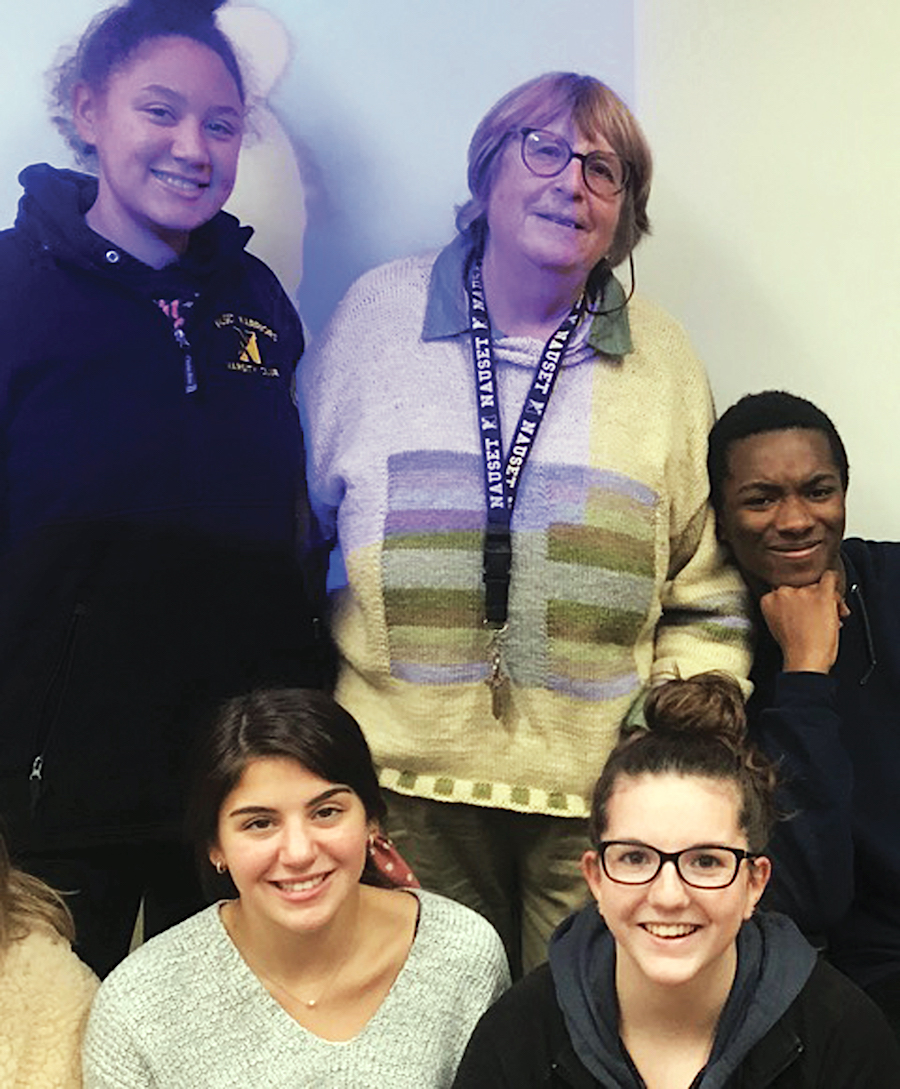

Lisa Brown, a veteran teacher at Nauset Regional High School in Eastham, has a popular class with a curriculum of her own making called Exploring and Respecting Differences (EARD).

Brown has observed firsthand how much interaction there is between children of different ethnicities in the school. She is able to consider how the notion of a “racial” divide affects them, and how to steer them away from unexamined assumptions.

Over the years the school’s demographics have shifted somewhat to include Jamaican, Puerto Rican, Indian, and, mostly adopted, Asian kids.

“Here’s the thing I observe at the high school,” Brown says. “It’s not so much about the color of the skin, but that cultural values are different. The trick at the teenage level is to find the common denominator of values — where is your own sense of right and wrong? If someone else’s is different, it challenges your sense of self.”

She has an effective exercise that she uses to allow students to practice this kind of self-awareness.

“I ask a question, usually one already generally debated in this country,” she says. “For instance, ‘Is it okay for a parent to spank — not beat — their child if they do something wrong?’ Then I split the room in half into a ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ side, and each student must go stand at one or the other, depending on what they believe about the question.”

No ambivalent side is allowed.

Then, by searching for values that they have in common, each group has to come up with a statement that they unanimously believe justifies their opinion.

With this experiment, cultural rules are exposed.

Most of Brown’s Jamaican students went to the “Yes” side: “You don’t talk back to your parents.” Most of the American kids went to the “No” side: “No, it’s not okay; it’s child abuse.”

Brown recalls a Jamaican student telling her, “I spent the night at an American friend’s house, and she was talking back to her mother. I stood there with my mouth open — I never talk that way to my mom!”

“A lot of the Jamaican kids who take my class are deeply valuing their education,” Brown says. “They see it as advancing themselves in a new and sometimes bewildering society. And they are working hard to assimilate. Assimilation means they buy into the rules, conditions, expectations of the school.”

Although the EARD class itself becomes a kind of common denominator, connecting students from different cultures, Brown wonders how to get them to hang out outside of class. She’s beginning to see small changes.

“More and more kids,” she says, “are venturing out from their potentially stereotyped groups.”

In part, she feels it’s because the class conversations are more often based on recognizing differences in culture rather than race.

“I give them a variety of perspectives and see where they land in the continuum,” she says. “It’s always about finding a common denominator. Once kids have come to recognize that cosmetic differences are cosmetic and that cultural differences exist — sometimes profoundly — if they can uncover enough values in common, then they have a basis to establish relationships outside of class.”

Brown starts out having students explore their own tendencies to stereotype. Following that eye-opener, she shows how stereotyping fuels the beliefs of hate groups. And then: how hate and fear, born of deliberately distorted stereotypes, can devolve into cults that depend on rigid tenets and threats to keep their groups in line.

From there, she takes the class through the escalations of conflict and how to apply methods of conflict resolution.

“My job,” Brown says, “is to create a platform for problem-solving, then let the kids do it. It’s not about ‘race’ anymore. We have to have it be about cultural differences.” And self-discovery.

“Who,” she asks them, “is your ultimate authority? Your parents? Your friends? Your conscience? Your religion?”

Whatever the answer, it comes from the kids. “I create the template; they draw the pictures,” Brown says. “I’m not the docent — they tell me what the picture is. Then I ask, ‘What more can you tell me about it?’ ”

An ultimate goal of the EARD class is for students not only to welcome differences and reject built-in prejudices but to find the indisputably elemental things they share as classmates, as teens, as people, and as a society.

“They all say, ‘I would absolutely never kill somebody!’ What else do they have in common? It’s a fact, they all agree, that every kid opens the refrigerator as soon as they get home,” Brown says, laughing.

Some may find leftover rice and beans in the fridge, others a tuna sandwich. “Okay,” Brown’s students might suggest, “Bring yours in next time. I’ll sample yours, you mine, and we’ll see if we like each other’s lunch.”

“It’s not a shared value,” Brown says, “but it’s a habit, a shared habit. And that’s where a class conversation can begin.”

When Brown teases out a subject, then sits back to witness the unfolding, she is demonstrating a powerful key to conflict resolution: a witness’s capacity to shut up and listen.

“In our class,” she says, “we have an acronym: W.A.I.T.” (Why Am I Talking, or Texting, or Tuning out….)

It’s a thought-provoking concept. And Brown’s class is meant to provoke thought.

That’s important, because from nation to neighborhood, how we grapple with our differences now is the crucible from which the shape of our collective future will emerge.

Luckily, our schools have the potential to embody this crucible, allowing us an opportunity to recognize how our assumptions act themselves out in our children, and, hopefully, how to bridge misunderstandings before they calcify once more into adult beliefs.

In time, it may be those students who’ll replace a few worn and overloaded words in the national mind with their own acronym: W.A.I.T. — and then watch where it takes us.