Cowboy Junkies Make Their Own Kind of Music

Is it country? “New” country? Country-rock? Folk? The sound of Cowboy Junkies is tough to pin down. In a world where so many acts sound interchangeable — and are engineered to appeal to a certain demographic — Cowboy Junkies are practically a genre unto themselves. They will perform at Payomet Performing Arts Center in North Truro on Saturday, Sept. 24.

When Cowboy Junkies released their second album, The Trinity Session, in 1988, it sounded like nothing else in a popular musical landscape dominated by Madonna, Prince, and Michael Jackson. There was something quietly revolutionary about them, even if their highest charting single, “Sweet Jane,” was a cover of a nearly two-decade-old Velvet Underground song. (Lou Reed called it the best cover of it he’d ever heard.)

They were also a distillation of some of the alternative musical currents of the time. The neo-folk vibe of Tracy Chapman and Sarah McLachlan was carried forward — some might say perfected — by vocalist Margo Timmins, whose voice let you know that she had seen it all and then some. The music of Margo’s brothers, Michael (on guitar) and Peter (on drums), paired with Alan Anton’s brooding bass line, took advantage of then-new compact disc technology, each spare strum and tap emerging like spirits from the perfect silences that CDs allow. In hindsight, you could even argue that their windswept acoustic sound helped mark the beginning of the end of ’80s synth-pop and was a harbinger of the grungier ’90s that lay around the corner.

Earlier this year, the band released its 19th studio album, Songs of the Recollection. Even though they’ve enjoyed popular success over the past four decades, Cowboy Junkies have never been a pop band. Like a handful of other artists — Aimee Mann and Lucinda Williams, to name two other mavericks who have also performed at Payomet — they’ve set their own rules and their own pace. And they still sound like no one else.

Tickets start at $35 and can be purchased at Payomet.org. —Richard Read

Sallie Kane Wishes You Were Here

Sallie Kane’s landscape paintings feel like postcards from an old friend: intimate in scale and descriptive of a particular place. A selection of her new work will be on view at the Captain’s Daughters (384 Commercial St., Provincetown) through the end of October.

The intimacy of Kane’s paintings has something to do with where she makes them: on her kitchen table at home. “I never thought I had to rent a studio,” she says. “Everything I need to make my art is out there in the landscape — and right here in my house.”

A self-taught artist, Kane was originally drawn to printmaking until she had an epiphany while taking a monotype class several years ago. “I suddenly began to get frustrated with all the rules,” she says. “Printmaking involves following certain steps. And I realized the only part I really liked was applying oil pigment on a plate.”

After experimenting with watercolors, Kane now mostly works in oil on panel. She calls her pieces “memory paintings.” They start with walks around the beaches and dunes of Provincetown, especially in the off season. “I like to leave my house very early in the morning, even before the sun comes up,” she says. “No one else is around, and you see things that no one else sees.”

During these walks, Kane photographs transient moments: a flurry of snow on an empty road, the brilliant flash of a fire-colored sunset over the harbor. Kane then makes graphite sketches of the scenes on panels, which are sealed before being painted over for the final work.

Like many artists on the Outer Cape, Kane is fascinated by its ever-changing quality of light. “It’s a cliché to say that,” she says. “But I never get bored of it. It’s always different out there. Even if I painted every day for the rest of my life, I would capture only a fraction of everything I see.” —John D’Addario

Michael Mazur’s ‘Seaside Studio’

Artist Michael Mazur’s former studio in the East End of Provincetown, where he worked for more than 30 years before his death in 2009, seemed to float at high tide, nestled as it was into the shoreline astride the home and gardens he shared with his wife, the poet Gail Mazur. Working on the water, Mazur created astonishing gestural paintings of the sea that are as rooted in the natural world of the Outer Cape as they are mysterious and transporting.

“Seaside Studio,” on view at Albert Merola Gallery (424 Commercial St., Provincetown) through Oct. 5, is a collection of Mazur’s paintings, mixed-media pieces, drawings, and monotypes from the early aughts that are rich in autumnal color and ethereal in shape and line. The works depict the tidal dance of the bay in all its characteristic swirl.

Rocks are scattered and linked along the shoreline; underwater, they’re rendered as jewels. Each piece in the series is a version of the infinite variations of the sea and its contents. Mazur’s layered color-wash technique creates works that are permanent records of temporary perfections.

Splitting his time between Provincetown and Cambridge, Mazur made profound contributions to contemporary art. His work is part of many prominent collections, including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. He taught printmaking at Harvard for 20 years and is a touchstone for many artists who have lived and worked in Provincetown.

“He was tireless in his work ethic,” says gallerist Albert Merola. “He was never without pencil or pen and paper, and he was drawing up until the last days of his life. Mike was a special force in the Provincetown arts community, and his presence is missed to this day. He was an inspiration to us all.” —Kirsten Andersen

Floating Along With Jay McDermott

Jay McDermott has been working on some of his paintings for years, while others took form just weeks ago. Fifty of them are on view at the Provincetown Commons (46 Bradford St.) through Oct. 2, with an opening reception on Saturday, Sept. 24 at 5 p.m.

A general dentist who has been “painting in earnest since 2000,” McDermott is fascinated with color. His most recent work is a series of nine boats in which striking hues and expansive shapes make for a series of lively and deliberately flat maritime scenes. Drawn to boats for their combination of simplicity and fun, McDermott sees them as ideal subjects because of their variety.

A chartreuse sky and teal sea in one painting, followed by gray cloud cover and a vibrantly royal blue ocean in another nearby, make McDermott’s boats appear to move together, captured in distinctly toned snapshots as they float toward a shared destination.

McDermott enjoys working in series, he says, because each boat “has its own voice, and then it needs somebody to talk to.” While the boat series is distinct for its cheerful charm, McDermott’s show also features his forays into interpretive abstraction. Tides Rising, a larger work that he describes as having “moderately serious undertones,” has been in process for four years.

Before beginning to work on his current show, McDermott and his wife spent time in Santa Fe, where he was inspired by the arid Western landscape. He studied with Bailey Bob Bailey early in his painting career, and the two still occasionally see each other around town. In Santa Fe, his teacher had him tape his paintbrush to the end of a yardstick and make shapes on the canvas from three feet away to loosen his stroke.

McDermott says it can be hard to know when a painting is finished. The final painting in the series, Mail Boat, was completed just three weeks ago. He changed its central panels of color several times. He felt satisfied and tightened the edges only when “the colors danced with each other.” —Sophie Mann-Shafir

Jim Youngerman’s Surrealist Shadows

If Jim Youngerman’s work looks strangely familiar, it may be because you dreamed it once — or maybe it’s because you remember the 2021 Swim for Life T-shirt, which featured one of his paintings.

A longtime participant in the Swim (and often one of its leading fundraisers), Youngerman is showing his work at Aline Interior Design Studio (101 Route 6A, Orleans) from Sept. 23 through Thanksgiving. It’s his first show on the Cape since the 1990s.

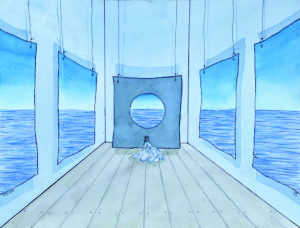

The exhibit features the surrealist shadow play that makes Youngerman’s paintings appear full of echoes, as if there were many potential compositions flickering across the surface all at once. His “Outside-In” series began in 2020 as an exploration of sheltering in place during the first months of the pandemic, when Youngerman’s isolation in Key West inspired him to consider the ways that exploring the coastline in solitude blurred the line between outdoor and indoor life. In one work, brightly colored waves move across hanging canvases that act as portholes through which a seabird perches on a bed and a dining chair floats out to sea.

In contrast, his “Noir” series — appropriately in black and white — depicts city streets thick with reflections of the objects, animals, and people who inhabit them. Gray tones seem to flicker from all angles at once.

The intricacy of Youngerman’s watercolor, ink, and pencil compositions gives the impression of careful planning. But the artist says his paintings involve very little “preconception.” Describing his process, he quotes E.L. Doctorow: “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” Similarly, Youngerman says, he works one stroke at a time: “If I can get one image on the piece of paper and start riffing on that image, that’s how the paintings develop — although they look like something else when they’re completed.” —Liz Wood