Two years ago, artist Kurt Reynolds responded to a call for submissions for artwork commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing in Provincetown. But the piece he created became more than that.

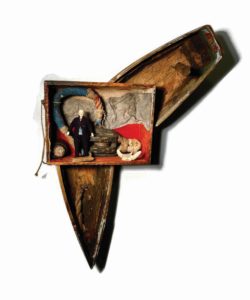

Titled How Far Is the World, it’s currently on view in his solo exhibition at the Provincetown Commons. It incorporates found materials to build a poetic narrative not only about the history of Provincetown but about his own place in the world.

The composition is a sort of diorama with a figure at its center framed between two pieces of a boat that seems to be broken, which Reynolds says he used “to emphasize the chaos and fear of being at sea.” Like the Pilgrims — and Reynolds himself — the vulnerable figure looks determined to explore new horizons and the possibilities that lie beyond them.

In creating the work, Reynolds says, he began with the question “How do we get to a world that’s going to be better?” It’s one that has resonated through much of his life, fueling his activist artwork at the height of the AIDS crisis and fostering his career as an art therapist.

Reynolds grew up in Chelmsford and Attleboro, the son of a World War II veteran. “I’m of that post-war generation,” he says. “Many of us suffered from the wounds that occurred in the young lives of our fathers. I didn’t speak until I was four; I had autistic-spectrum symptoms and I was very sensitive to sound. I developed defenses for self-soothing.”

He says those defenses included making high-pitched humming sounds, absorbing himself in the study of specific objects, and making art. “In my world, which was pretty internal, objects became really instructive to me,” he says. “I was fascinated with things and what they meant to people — the concept of a keepsake, the things we prize.” (Reynolds says he particularly remembers loving his grandmother’s round plastic earrings.) “Those objects for me were imbued with a living story.”

During his years in Catholic school, Reynolds began making personal shrines to various saints. “I got to stay in during recess,” he says. “I developed skills, and the nuns would praise me for making these beautiful things. It kept me safe.”

A sense of the devotional has also characterized much of the work Reynolds has created as an adult. There’s a reverence for the found objects he incorporates into his assemblage relief sculptures. “It’s very important that I allow the objects to speak for themselves,” he says. “They too have had a life before me. They’re imbued with the energy of the lives they were once part of.” It isn’t surprising to learn that Reynolds once owned an antiques store on Charles Street in Boston.

In Mercy and Peril, Reynolds uses an antique wooden prosthetic as the base for a figurine of a one-legged sailor. There’s an evident synchronism in the composition, and the previous lives of both objects are resonant with mystery and human drama.

In other pieces, Reynolds uses found objects to build fictions, often enclosing them in diorama-like boxes that recall the work of Joseph Cornell. Mercury in Free Fall references mythological narrative, and another work — The Puppet and the Jester on the Last Day of Childhood — reads like a miniature theater, complete with a painted backdrop and actors.

In still other works, Reynolds lets the objects speak for themselves: “Sometimes, I don’t want to be in their way,” he says. The effect can be minimalist, almost Duchampian, as when he hangs a simple piece of frayed rope on an oval-shaped piece of wood. Elsewhere, as in Year After Year, he takes a more formal approach: the piece explores the spaces between three wooden planks, which he says were used to cover a pipe on Commercial Street. The insertion of bronze-cast whale vertebrae into the surface of the planks emphasizes its connection to a particular place. “I’m using materials as an echo of where I live,” he says.

Reynolds moved to Provincetown in 2013 after living most of his life in the Boston area, and his work since then has referenced both the town’s nautical history and his own personal experience. Several pieces in the show incorporate parts of musical instruments like piano keys and cymbals; one work, Migration, depicts a flock of violin cases. They recall the time in Reynolds’s adolescence when he discovered folk music. “At 11 or 12 I picked up a guitar,” he says. “Music became my way into the world. Finally, words meant something to me.”

Music and art have been anchors throughout his life. During the height of the AIDS crisis, he played music at memorial services, was active in social work, and began creating sculptural pieces memorializing the lives that were lost to the disease. One was a paint box covered with the obituaries of artists who died of AIDS. Another explicitly illustrated the “cocktail” of 26 pills he took daily as a long-term HIV/AIDS survivor, complete with an olive-topped martini glass.

Although the newer work in Reynolds’s current show doesn’t address the AIDS crisis directly, it was likewise created during a pandemic — and is still concerned with social and political issues. “I’m using objects from the past to address issues in the present,” he says. “Things are threatened now: our liberties, our freedoms, our oceans.”

Reynolds addresses contemporary environmental concerns in a piece titled As the Sea Goes Silent, which evokes the fragile sonic environment of the ocean by using pieces of musical instruments to construct a sea creature. He says he was inspired by learning about the effects of noise pollution from ships, and his own sense of the musicality of whales. It’s a continuation of the kind of personally influenced activist art that has defined Reynolds’s practice for decades.

“For me, activist art is what’s on my mind,” he says. “It’s what’s in my heart.”

How Far Is the World

The event: An exhibition of mixed-media assemblages by Kurt Reynolds

The time: Through Oct. 2; conversation with Kurt Reynolds and co-curator Pete Hocking on Sept. 17, 4 p.m.

The place: The Commons, 46 Bradford St., Provincetown

The cost: Free