This month I asked Alexander DuToit, a senior at Nauset Regional High School, if he’d “Mad Lib” a poem — that is, take an existing poem and swap out everything in it with his own words, saving its syntax and punctuation, to create a new poem. I’m glad he said yes.

Like Agnes Mittermayr, whose “Arrivals Hall Poem” was published here in February, Alexander chose Sam Hamill’s “Black Marsh Eclogue.” (You can find the original at poets.org.) Having the same poem chosen twice allows us to see what different work can arise from the same source. Mittermayr’s poem was about returning to Austria to see her niece after a long absence. Alexander’s stays closer to home, discovering the magic in a darkroom enlarger.

Why has this poem inspired two writers? Maybe because it describes a single instant that connects to something vast — and, as Alexander told me, “It isn’t wicked long!” It gives enough space to say something, though, and he liked that it described something seen. An experience rather than a feeling.

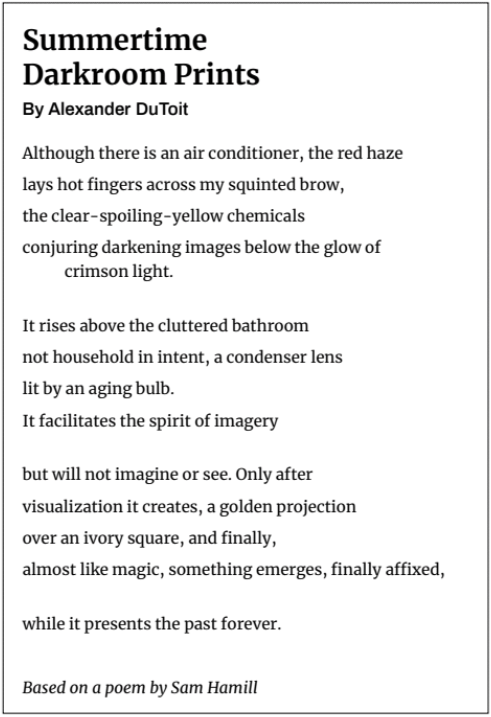

Both poems begin by rooting us in a particular place, starting with their titles. Sam Hamill’s “Black Marsh Eclogue” begins “Although it is midsummer” while Alexander’s “Summertime Darkroom Prints” opens with “Although there is an air conditioner.” I love this humorous acknowledgement of summer’s muggy swelter and the way Alexander sets us in the isolated world of the darkroom with its red light and chemical bath, so diametrically opposed to the wide marsh horizon of Hamill’s poem.

I had a chance to chat with Alexander during his lunch break between viola practice and volunteering for the Center for Coastal Studies. He said he’s never really written poems before, though for a while he was typing out brief observational scenes on index cards, which sounds a bit like poetry to me. When I asked what was difficult about writing this poem, his first answer was “identifying the parts of speech” so that he could accurately replace them with his own thoughts and words — spoken like the exacting student I know him to be (and showing the precise mind necessary for the finicky work of developing and printing photographs).

Alexander discovered that writing the poem was like working in the darkroom: it was a process that doesn’t happen without a human mind and hand, so unlike the digital tools we use with all their invisible algorithms.

At first Alexander thought he’d describe the process of making a print in the darkroom but said he ran out of room. This was frustrating, but in the end it worked to keep the focus on the enlarger itself rather than the print. Often, when writing poems and trying to describe something in more detail beyond what was first thought necessary, it happens that metaphor and resonance naturally arise, and this is absolutely true in Alexander’s poem.

I love how both he, bent over the light and the fixing chemicals, and the enlarger itself, rising above “the cluttered bathroom,” become the hunting heron of Hamill’s poem. How did Alexander know to invert the light of Hamill’s poem with the darkness of the photo developing process, the way Hamill’s poem goes from stillness to motion with the idea of fixing motion into preserved stillness? It may have been instinctual, as most good moves in poems often are: good poets have the gift of recognizing when instinct rings true.

What Alexander appreciates about nondigital photography is that he’s able to “see something, see it again later on the negative, then again on paper, and it’s different each time. You forget what you take,” he says. Later, “you rediscover it when you develop it and you find a scratch on the negative,” he adds wryly. It’s unsurprising that time comes into play at the end of Alexander’s poem.

In Hamill’s poem, the heron takes off from the marsh and “pushes the world away.” Alexander turns from the heat and light of summer to the contrived lightlessness of the darkroom, pushing the world away in order to bring it forward in prints, which will “present the past forever.” I am amazed by the beautiful rhythm in that line, which is a joy to speak aloud and holds the smart, accurate doubleness of “present.” My conversation with Alexander reminds me that even if there are scratches or flecks of dust on that preserved moment, those, too, are part of what is preserved.