Handwritten signs are part of the visual memory of most any American road trip, each one a piece of artwork conveying the maker’s touch and earnest intention. Like most handmade things in our culture, these signs have been threatened by digital processes and mass production. Yet in many places they still hang, their longstanding popularity owing perhaps to their simplicity. All one needs is a flat surface, a brush, and some paint to convey a message to the world.

Here on the Outer Cape, unpretentious hand-painted signs are as much a part of the local landscape as fried seafood and views of the Atlantic. A performer like Ani DiFranco might find her name on a slick poster or in neon lights in another part of the country, but when she plays at Payomet her name is hand-scrawled on one of Payomet’s red-lettered, low-fi roadside signs.

Katy Kmiec purchased Hatches Produce in downtown Wellfleet 10 years ago from the late Lauren McClellan and continued the tradition of hand-lettered signage to advertise her products and prices.

“Some of the original signs are from Lauren,” says Kmiec. “She created this atmosphere, and my goal was to keep it.” Signs advertising everything from popsicles to lettuce varieties are made by employees.

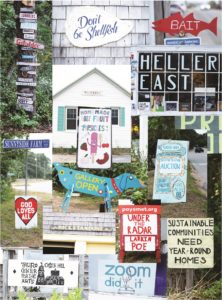

In the National Seashore, houses are marked by family names painted on strips of wood and nailed to pine trees. Close to the entrance to Newcomb Hollow Beach in Wellfleet, a stack of signs on a tall pitch pine is a much-photographed collection. Before Google maps, they likely served to direct visitors. Today their appeal seems more aesthetic than practical.

When Jude Ahern decided to run for the Wellfleet Select board, she enlisted Curt Ribb, a professional sign painter in Chatham, to help her make hand-painted campaign signs. Ahern, an art appraiser, says she has long admired the use of text in works by artists like Edward Ruscha and Jenny Holzer. Besides, she says, “I don’t like plastic signs.”

Some of her messages were simple: “Vote Jude.” Others, like “Vote No on Everything,” were more provocative. “No nice signs ever changed anything,” says Ahern.

Ribb says he found his way to sign painting through the theater. “I learned the basics volunteering at the Chatham Drama Guild in high school,” he says. “A couple of old-timers wore all the hats, and they taught me the basics of simple sign layout.”

Ribb, 40, continued his education by attending a few workshops, reading, and watching YouTube. “I can go on YouTube and watch an 85-year-old sign writer for a half hour before going to sleep,” he says, adding, “It’s usually the most interesting thing I can find on the internet.”

Ribb, who is also a florist and welder of shellfishing equipment, painted “Heller East” on the windowpanes at Julie Heller’s gallery in Provincetown. Ribb considers the piece an example of his style. His text follows strict rules, with consistent spacing and positioning of the bottom, mid-point, and top of each letter. It’s a stylish image, both disciplined and hand-drawn.

Dan Crowley began summering in Eastham in the 1960s as a young child. “From when I was a young kid until the early ’70s, everyone had a name for their cottage and referred to it that way,” Crowley says. He summered at “Rosebud,” across from “Just Right” and “Even Better.” The names were hand-painted on plain pieces of wood, he recalls, and though many of those signs have been replaced by numbers or fancier, more formal signs, “the hand-painted sign just seems more down-to-earth, original, and spontaneous,” he says.

At Day’s Cottages in Truro, the tradition of naming cottages continues, with each cottage bearing the name of a flower, hand-painted in red, black, or purple letters on a white piece of wood. They initially read as uniform, but a closer look shows variations in spacing, color, and weathering. Further down the road, a North Truro bayside home has a sign above the garage reading “Bickstandune” in drop-shadow lettering, the font a vestige of midcentury graphics.

Further into Truro, Castle Hill signs begin to appear around the Edgewood Farm campus and in the town center, created by intern Claire Harpell and studio manager Meghan Murray. These sandwich-board signs announce upcoming events in colorful words and images. Cherie Mittenthal, the executive director, says that sign-making has always been a Castle Hill tradition.

Murray approaches the job with care. Sign painting, she says, “ties us to the history of this place.”

“We have a few times to speak and be heard,” says Ahern. “Sometimes a sign says it all.”