Cookie Mueller and her friends were cold. They were in Provincetown, it was the winter of 1970, and Mueller, who is best known for acting in John Waters’s films, and who died of AIDS in 1989 at 40, was living in a clapboard saltbox house with four roommates, one of them the drag queen and camp icon Divine. The house was barely insulated, the toilets were frozen, and Mueller could see her breath.

One night in late December, Mueller’s roommate, Marnie, in what seemed like a trance, took all her roommates’ clothes out of their bedrooms and cut them into little scraps. Their wardrobes sat in a heap in the middle of the living room like spaghetti in a bowl. Wearing curtains and blankets, the roommates drove Marnie to the hospital.

“She was admitted and dressed in a clean white hospital gown and ushered into warmth and medication,” Mueller wrote of the scene. “Seeing this, we were all pretty jealous.”

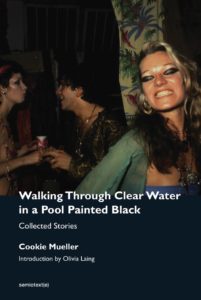

To say you’re jealous of a friend you’ve just delivered to a mental hospital might seem insensitive, even callous. But, as Olivia Laing writes in an introduction to the new, expanded edition of Cookie Mueller’s Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, published by Semiotext(e) in April, Mueller understood what writing could do for pain: “Pain doesn’t need to be spelled out, but rather defanged.”

Mueller could take “the most plainly terrifying or distressing material” and, by writing about it in her playful, snappy tone, Laing writes, “make it something that can be appreciated and shared, a communal pleasure rather than a private humiliation.”

The new edition comprises almost all of Mueller’s writing. There are short stories and her art criticism, published in Details magazine. And there’s her advice column, “Ask Dr. Mueller,” which first appeared in East Village Eye. When someone writes to Mueller that women complain about his manhood being too large, she advises him to become a homosexual. “Nothing is too big for an experienced, fun-loving gay man,” she says. Her advice for just about everything else is to travel to Italy.

The bulk of the book, though, is made up of Mueller’s personal essays, which amount to an oddball memoir about a life lived the way young people, with the crutch of the internet and on an I.V. drip of 21st-century anxiety, no longer do. Mueller’s was a life without hesitation and on the road. It didn’t make much sense to her to plan ahead — you could always wing it later.

One of the early essays, “Haight-Ashbury — San Francisco, 1967,” is an overture for the misadventures to follow. Mueller, 18 at the time, is awakened by an earthquake at 10 a.m., which she calls “an uncivilized hour.” And even though it’s “too early to get up,” she goes out looking for “something new.” She hops inside a school bus where five girls who seem to have “faulty brain synapses” keep talking about a magnificent man named Charlie. They tell Mueller she really must stick around and meet him. She says she has to get going. A few years later, she realizes “Charlie” was Charles Manson.

She passes by a woman who, having slept with Jimi Hendrix, is extolling his virtues. “I walked on by,” she writes, adding she’d been with Hendrix the night before. Around noon, she finds friends in Golden Gate Park and they share a bottle of wine, then she goes to a Grateful Dead concert, then a peyote ceremony, then a séance. On her way home, she is raped at gunpoint. “It wasn’t even done well, and he was stupid besides,” she writes.

If Mueller’s way of living is bygone, her way of writing may well be, too. Sentences today are florid by comparison, full of tidbits accessible to writers via a simple Google search. Mueller’s sentences have a high speed-to-power ratio: when her friends keep telling her that time will heal her heartbreak, she writes, “Time took too much time.” When she does deploy a second clause, the important information hangs off the comma, like a twist of the knife: “I lied because Alice didn’t like Sam using heroin, especially if she didn’t get some of it.”

One of her longest and most beautiful sentences is about her first trip to Italy: “I had planned to do a lot of writing and serious things like that but after a few more days I realized that I’d have to shelve this idea because there was the water and the sun and all this wine to consume and food to get fat on and nightclubs to dance in.” The breezy rhythm establishes Mueller’s sense of delight at the world.

Her words are unexpectedly moving — perhaps because one realizes on close inspection that Mueller’s description of a carefree existence is actually meticulously crafted.

Mueller, even at the end of her life, when she was suffering from AIDS and a heroin addiction, filled words up like balloons. In “A Last Letter,” her furious elegy to the lives AIDS stole from us, she writes, “These people are dying in a whisper.” That is so, but Mueller’s words reverberate, as if whispered closely into a microphone.