In 1960, Claes Oldenburg left New York City to spend the summer in Provincetown, where, according to his own testimony, he washed dishes. He also constructed 70 flags out of driftwood, metal, and paint, which, he explained in a Museum of Modern Art 2013 retrospective on his early work, “represented a new direction because they were somewhat like paintings, but three dimensional and very rough.”

That 1960 new direction has been characterized as a breakthrough year for Oldenburg, for upon his return to New York from Provincetown he launched two exhibitions, one in his Lower East Side studio called The Street and the other, called The Store, held in a series of small shops, also on the East Side. After those two shows, wrote Fred A. Bernstein in the Washington Post, “Mr. Oldenburg was an art world star.”

Oldenburg’s Provincetown interlude was instrumental in the transformation of his art, which included painting, ceramics, soft sculpture, and monumental public sculptures depicting ordinary objects on a large scale — like the giant binoculars he contributed to a Frank Gehry-designed building for the Chiat/Day ad agency in Los Angeles.

In addition to incorporating sculpture into the canon of Pop art, Oldenburg was also a writer. Before, during, and soon after his Provincetown summer, he produced a sprawling Whitmanesque poetic manifesto on art and a pamphlet deploying a mash-up of literary forms. Mixing names from classic literature (Crusoe and Faust, for instance) with graphic depictions of bodily functions and surreal physical transformations, Oldenburg’s writing enacted the ambitions and energies of early 1960s avant-garde and popular culture.

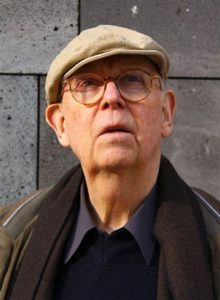

Claes Oldenburg died on July 18, 2022 at his home in Manhattan. The cause was complications of a fall. He was 93.

Oldenburg was born in Stockholm on Jan. 28, 1929. His mother was a singer and his father a Swedish consular official. The family moved to Chicago in 1936, then back to Europe before returning to America. Oldenburg studied literature and art at Yale, graduating in 1950. He then returned to Chicago to work at the City News Bureau and to study at the Art Institute.

He became a naturalized citizen in 1953 and moved to the Lower East Side, a neighborhood where he rubbed shoulders with beat poets and Pop artists in an environment he found “most creative and stimulating.” While engaging in artistic experimentation among his peers and on New York’s streets, Oldenburg frequented the library at Cooper Union, cultivating his senses and his intellect.

It was at Cooper Union that he held his first exhibition of figurative drawings in 1959. A year later, in a collaboration with Patty Mucha, whom he married in 1960, he created one of the first performance art events, “Snapshots From the City,” staged at Judson Memorial Church. That summer he came to Provincetown.

“One of the nicest things about Provincetown,” Oldenburg said in a MOMA recording, “it has a great beach. And because it sticks out into the Atlantic on a right angle, it collects just about everything that comes up along the shore.” Oldenburg, too, started to collect what came up on shore. “I was working as a dishwasher in the evenings,” he said, “but during the daytime I would go down to the beach and gather wood.”

Rather than shaping the wood into abstract forms, Oldenburg said, he wanted “to give them [the pieces of wood] the character of the place where I was staying. I wanted it to be patriotic. So, I made them into flag scenes. They’re like postcards with flags on them, only translated into wood.”

His matter-of-fact, incisive statement captures something essential about Oldenburg’s art, which combines a gritty sensitivity to the particular objects that determine the character of a place with an awareness of the economics that determine the possibilities for good or ill in a life lived there. The fusion of driftwood and post cards articulates in inchoate form the animating energies of his later more eclectic and monumental work.

In the catalog for an exhibition called “An Americanization in Modern Art” (Berkeley Art Museum, 1987), Sidra Stich wrote: “In Provincetown, flags are everywhere, testaments to both traditional patriotic faith and vacuous contemporary cliches. Oldenburg’s flags capture both aspects and affirm an acute responsiveness to the seaside environment. The flags have the life-and-death quality of nature, the awesomeness of survival under harsh conditions, and a witty engagement with simple, fond treasures.”

By 1969, Oldenburg was the subject of MOMA’s first major Pop art show; in 1970, he and Patty Mucha divorced. In 1977, he married Dutch art historian Coosje van Bruggen, with whom he collaborated on his giant polychrome outdoor sculptures until her death in 2009.

According to one of Oldenburg’s biographers, he “was strongly influenced by the writings of Sigmund Freud and underwent an intense period of self-analysis between 1959 and 1961.” During that time, as Oldenburg himself put it, “I thought the moment needed a poetic ode in the footsteps of Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl.’ ” In response to that need, he wrote, “I am for Art,” which he described as “a slightly satirical ode or paean to the possibilities of using anything in one’s surroundings (mostly urban) as a starting point for art.”

The ode states: “I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself. I am for an artist who vanishes, turning up in a white cap painting signs or hallways.”

He lived such an art. As Deborah Solomon wrote in a recent appreciation: “Oldenburg was never a public figure, and his art is more recognizable than he was.” Nonetheless, she added, “He will no doubt be remembered as a top-drawer artist and one who, like his ambassador father, was a force for world democracy. But funnier.”

Indeed, as the editor of an appreciation on the website “Frieze,” wrote, “In a series of studio notes Oldenburg made in 1960, he wrote impatiently: ‘Everyone is making paintings and being so frigging artistic.’ He, instead, was making crude plaster reliefs of everyday objects, assembling deadpan American flags from Provincetown driftwood and helping give birth to the happening. ‘Bad taste’, he noted, ‘is the most creative thing there is.’ ”

Oldenburg is survived by two stepchildren, Maartje Oldenburg and Paulus Kapteyn, and by four grandchildren. He was predeceased in 2018 by his brother, Richard, who was director of the Museum of Modern Art for 22 years and later chairman of Sotheby’s America.