WELLFLEET — Marcel Lajos Breuer — Lajkó to most people — was born in Pécs, Hungary into a cultured, middle-class family during the glory days of the Austro Hungarian Empire in 1902. His mother, the more influential parent, emphasized to the young Lajkó that education, travel, sports, and an appreciation of beauty were key foundations of a meaningful life. Into painting and math, Breuer enrolled at the Viennese Academy of Fine Art, but he was turned off by the rigid and overly theoretical air and soon dropped out.

At a friend’s suggestion, he instead joined in 1920 the avant-garde Bauhaus art school recently launched in Weimar, Germany. Breuer was immediately inspired by the free-spirited atmosphere — in a letter to his parents he mentions the grand time he had at a cross-dress party — and enjoyed the hands-on experience with different materials. Gifted and ambitious, Breuer quickly established himself as a star student and Bauhaus director Walter Gropius’s favorite.

Breuer became the youngest teacher of the Bauhaus’s prestigious faculty in 1924, after Gropius persuaded him to lead the carpentry and furniture workshop. Soon came a pivotal moment in design history: the 23-year-old Breuer was the first person to make furniture using bent metal. His revolutionary tubular steel chairs are celebrated classics of modern furniture today. There are various origin stories, but one inspiration was his bicycle’s sturdy handlebar after a fall, which led him to wonder if furniture could be made from bent metal.

In 1937, Breuer moved to Massachusetts to spread the gospel of modernism to a group of students who would later shape American architecture, including Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, and Paul Rudolph. Easygoing, funny, and brilliant, Breuer was idolized by his students. On the side, he and Gropius set up a practice together. Breuer’s residential houses softened the austere forms of the Bauhaus with long cantilevers and natural materials such as fieldstone walls, flagstone floors, and cypress siding. Using the New England vernacular as inspiration, he made an American suburban version of modernism that was original and beautiful.

The American public first heard of Marcel Breuer in 1949 when the Museum of Modern Art asked him to create a model house inside the museum’s garden. The exhibit’s mission was to show suburban middle-class Americans the modern way of domestic life. The elongated house with large horizontal windows was enlivened by a butterfly-shaped roof and a beautiful contrast of materials. The free-flowing space was meant to help a mother keep an eye on the children’s area, which was on the separate end from the parents’ bedroom. The light-filled rooms were fitted with Breuer’s own furniture and those of his famous contemporaries, including Eero Saarinen’s Womb chair and Charles and Ray Eames’s plywood side chairs.

With more than 80,000 visitors, the exhibit was a major success and shaped the way Americans viewed the modern home. It also inundated Breuer with new commissions.

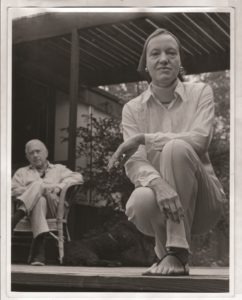

Together with fellow European emigré friends and their families, Marcel and Connie Breuer spent the summers deep in the woods of Wellfleet. They formed a secluded, free-spirited community infused with alcohol and spirited debates about art. Heavy on Hungarians, the Wellfleet crowd included György Kepes, the influential artist and M.I.T. professor; Serge Chermayeff, the Russian-born Yale professor of architecture; Walter and Ise Gropius; and Saul Steinberg, the Romanian-native cartoonist of the New Yorker magazine.

“You could do whatever you wanted here,” says architect Peter McMahon, head of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust. “Wellfleet was depopulated back then. Swim naked in the ocean, the bay, or the ponds. It was very cheap to buy land and the landscape reminded many of them of places in their past.”

Breuer’s Wellfleet cottage, which he designed in 1949, overlooks Williams and Higgins ponds and embodies his love of nature and craftsmanship: the delicate, wood-framed rectangular building is gently elevated in the air; from it juts an overhanging porch where he liked to serve his beloved goulash and chicken paprikash. Later, Breuer added two wings to provide more privacy and a darkroom for his photographer son. They fit perfectly but aren’t identical to the main building.

“Breuer was a genius,” says McMahon. “He doesn’t want to impress you with his architecture; it’s a conversation he is having with himself.” Breuer’s son Tamás is currently in the process of selling the house, which is in need of serious renovation. “We’d love to buy and restore it and then turn it into three artists’ residences, but the price he wants is way out of our range,” McMahon says.

“Hungarian culture came through the whole group. It was one of the things that held them together,” says Guy Wolff, Connie Breuer’s nephew, of his childhood memories of Wellfleet during the Cold War years, when this left-leaning bunch, some of them with past connections to the Hungarian Communist party, had to be vigilant.

“There was a lot of paranoia,” says Juliet Stone, György Kepes’s daughter. “We had to hide certain books in the basement — a history of the Spanish Civil War and leftist magazines. My father was very worried when I wore all black during a July 4th celebration. He wanted me to put on American colors, but I was a beatnik teenager.”

“The whole group was driven by this search for making something beautiful,” says Wolff. “If Lajkó was looking at the lake, he was seeing shapes. Their house had this quiet beauty about it.”

It’s ironic that Breuer is far better known today for his chairs than his buildings because he was emphatic about how he viewed himself. “I wanted people to forget my furniture and get to know me as the architect I am,” he said in a 1937 interview with a Hungarian newspaper. “I didn’t want to spend my whole life furnishing interiors.”

This article is adapted with permission from “Marcel Breuer’s World,” published on April 20, 2022 in OffbeatBudapest.com, of which Tas Tóbiás is the editor.