PROVINCETOWN — For her family and friends, Veronica Silva’s 80th birthday party on June 15, 2012 was more of a living funeral than a celebration, recalled her son David Silva, 59, an owner of the Red Inn. “We’d get all choked up and start crying,” he said.

But Veronica would have none of it, despite her weakness and difficulty with the simplest tasks, like eating. “She wasn’t going anywhere until she had her share of time with all 11 grandchildren,” David said.

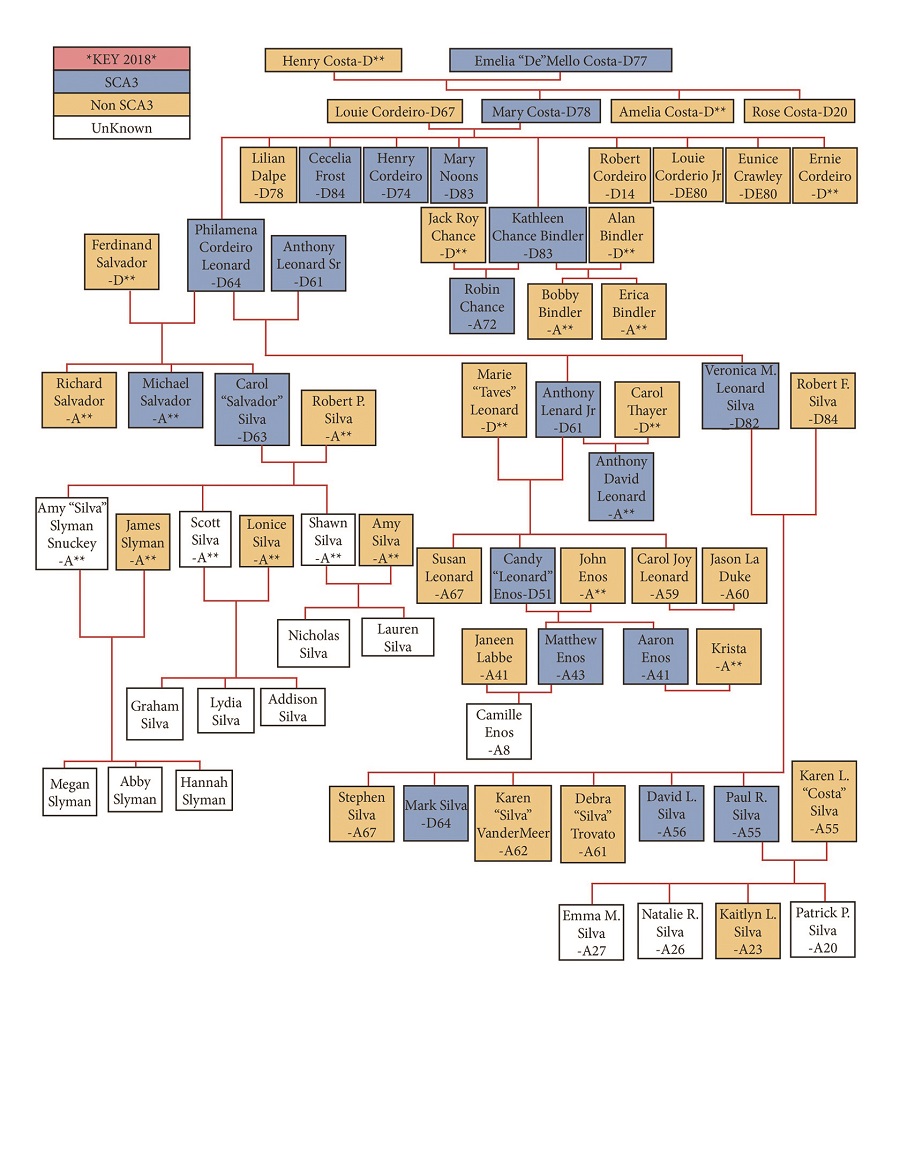

Two years later, Veronica died of Machado-Joseph disease (MJD), a rare neurodegenerative condition seen most often among people of Portuguese descent. Among the Silvas, whose ancestors have lived on the Outer Cape for decades, MJD is traceable to Veronica’s great-grandmother. It has followed the family for five generations.

The likelihood of children inheriting it from a positive parent is 50 percent. Veronica died in 2014 at 82. Among her six children, three, including David, have tested positive for MJD. In 2017, it took the life of her son Mark, who was 62.

MJD affects the cerebellum, a part of the brain responsible for muscle control, resulting in ataxia — or impaired coordination. Clumsiness is an early sign, often detectable in a person’s gait and in unexpected stumbles. Over time, the disease may cause slurred speech and fuzzy or double vision. Current treatments can control some symptoms, but a cure remains elusive.

By the time Veronica was in her 80s, she lacked the strength to sit up in a chair. She lost dexterity and could no longer tie her shoelaces or handle silverware. Swallowing became a challenge. She needed a special nebulizer on standby at every meal.

“They had to suck any particles out of her mouth and throat so she wouldn’t aspirate the food,” said David. “She’d do that two or three times a day, even if it was a bowl of ice cream, which she’d often have for lunch.”

On Oct. 22, the Silva Ataxia Foundation held its third annual fundraiser in memory of Veronica and Mark. The Red Inn teemed with old friends, coworkers, and colleagues who came to support important ataxia research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

David Is Diagnosed

Hints of David’s own MJD diagnosis emerged in his early 50s. He felt his golf game slipping. “I felt like I had little tremors,” he said. “But if you looked at my hands, they weren’t moving.” He had been a two-handicap player (averaging just two strokes over par per round). These days, his handicap is over 18.

Sliding onto a bar stool at the Red Inn in September 2012, David teetered and careened backward, his head nicking a window. Two inches closer, he said, and he would have crashed through the glass. It happened again the following August at a friend’s wedding. He lost his footing on a stroll with the bride, tumbling onto a large terracotta pot, which broke. A jagged edge cut his neck, earning him 12 stitches and 11 staples.

That accident led him to get tested at Mass. General Hospital. Dr. Jeremy Schmahmann, his neurologist, held up a finger, instructing David to track it while keeping his head still. Schmahmann jerked his hand quickly. “I could feel my eyes lag, trying to catch up to the finger,” David said. For a second test, David lay down and took off his shoes and socks. He was to make his right heel move up and down his left shin as fast as possible — but his foot kept drifting off course. A blood test checked for a DNA mutation associated with Joseph’s disease, and in January 2014 the results came back positive.

David told his brother Paul, who said, “God, I think I have it as well.” Later, as they were walking home from dinner, David noticed a hitch in his brother’s gait. A DNA test confirmed their suspicions.

After telling the other siblings, David implored them to be discreet. “Look, you can’t tell your kids,” he said. “You can’t tell anybody until Mom and Dad are gone because they don’t need the burden. It won’t do them any good to find out.”

Veronica’s condition was declining; meanwhile, her husband, Robert F. Silva, was losing his vision to macular degeneration. “But it was kind of a blessing,” David pointed out. “Because his vision was so bad, he couldn’t see how much Mom had failed. His picture of her was probably frozen in time.”

At Mass. General, David had met Dr. Vikram Khurana, who Silva called “the guy, in the research for spinocerebellar ataxia.” The family wanted Khurana to see Veronica. By then, in the summer of 2014, she was in no shape for a trip to Boston. But they were in luck. Though medicine has all but abandoned the practice, making house calls remains one of the “greatest privileges of being a physician,” Khurana told the Independent. Growing up, he said, he watched his grandfather and father, both physicians, get to know their patients that way. “We learn so much, being led into their place in space,” he said. “And it’s adventurous.”

That June, just weeks before Veronica died, he came to Provincetown.

Bad Instructions

In our cells, proteins regularly build up and break down, an ebb and flow that governs normal functioning. The ones destined to break down are tagged with a molecule called ubiquitin. If the cell needs to shift the balance and accumulate a certain protein, it dispatches enzymes that remove this tag. Ataxin-3, the gene involved in MJD, takes on this role.

For ataxin-3 molecules to operate as usual, “they need to fold into these exquisite shapes,” said Khurana. “When they’re packed in, they work terrifically.” But in MJD patients, the part of the genome that contains instructions for generating ataxin-3 contains a mutation. A fragment of DNA code — CAG — is repeated over and over, causing the cell, in making ataxin-3, to go overboard and make excess material. This prevents the enzyme from folding neatly. Its resulting form is sloppy — not to mention toxic.

Whether or not ataxin-3’s detagging function is related to MJD remains a mystery, Khurana said. But researchers know that misshapen ataxin-3 molecules tend to form sheets, which clump together in neurons. This bogs down the performance of the nervous system, and, over time, MJD symptoms emerge.

Medication can reduce tremors, prismed glasses can aid distorted vision, and therapy can mitigate speech and swallowing problems — but curing MJD is a much taller order.

Over the years, Veronica had donated “gallons” of blood to research, according to David. As Khurana monitored the final stage of her disease, she decided to donate her brain, spinal column, and other organs to his lab at Brigham and Women’s Hospital upon her death. Years later, when Mark died, he followed suit. And when Khurana was in town, members of the Silva family, with and without MJD, let him take skin samples. These contributions were instrumental in enabling Khurana and his team to break away from yeast, fruit fly, and mouse representations of the disease and create a more patient-centric model.

Khurana’s lab transformed the Silvas’ skin cells into stem cells. From there, they could produce neurons in a Petri dish. “We could build mini-brains and watch the disease unfold,” Khurana said. This approach also allowed him to address a crucial question about potential therapies for MJD: “Do I have confidence that this is a beneficial thing to do — in a human context?”

A potential gene therapy treatment is in development at the University of Michigan. Dr. Hank Paulson’s lab there is prodding cells to skip over the mutated region of the genome and make a leaner version of the protein. But to move forward on this, Paulson and his colleagues are awaiting the results of Khurana’s current project, which aims to create a “gold standard” brain cell.

Using the “molecular scissors” of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, Khurana’s lab is trying to snip out the damaged CAG stretch in neurons afflicted by MJD — in other words, to excise the repeats and produce what should, in theory, be a healthy cell, freed from the ataxin-3 mutation. This “gold standard” would offer Paulson’s team a point of comparison for evaluating whether their therapy can help cells achieve a normal state — and whether the treatment may churn up “off-target effects” in the genome, Khurana said.

Still Swinging

Paul was resigned when he heard his diagnosis. “When you grow up with it in your grandparents and your mother, it’s just part of the family,” he said, shrugging. “It’s really not as big a deal as one may think. Not a great thing to have, but there are worse things in life.”

Mark, on the other hand, harbored a deep “animosity” towards MJD. “And I understand why,” David said. “He was full of life — and he got cheated out of his 50s, which I’m living now.” Mark went from traveling the world with “just a pair of sneakers” to clutching a walker; eventually, after his legs atrophied, he was wheelchair-bound. He resented the nebulizer he needed after choking on oysters at the Red Inn. “It was bad enough that he couldn’t hold his own joints,” David said. “He liked to ‘partake.’ ”

David’s partner, Michael McDonald, recently asked him if he was bitter. David answered, “No, it’s not a ‘woe is me’ situation.”

He and Paul take after Veronica. They signed up for research studies at Mass. General, recently testing wrist and ankle devices that monitor ataxia from home. Paul is currently participating in a University of California San Francisco clinical trial involving the drug Troriluzole, now in its third phase. And they started the Silva Ataxia Foundation, which has raised over $300,000 since its inception.

“I was hoping that I’d be able to come here this year and say we finished the correction,” Khurana announced at the fundraiser last week, “but Covid did shut our lab down.” The “gold standard,” however, is on the horizon. Khurana’s lab is tackling the very last step.

Khurana recognized Allison Reeves, David’s second cousin, as a new member of his lab. Her grandmother was the sister of Veronica’s husband, so Reeves isn’t part of the Silva MJD bloodline. “But they’re my extended family,” she said, “loved ones I’ve always known.”

As part of her master’s thesis at Tufts, Reeves is conducting a biometric study of the Silva family, unspooling how MJD can present differently among different members. She hopes to attend medical school.

David, in the meantime, is hell bent on getting stronger, taking Pilates class twice a week and riding his recumbent bike. His drives at Highland Links have lost considerable distance, and declining eyesight has affected his depth perception, throwing off his golf swings.

Par at the links is 70. “But I can still putt really well, which is probably why I can still break 100,” he said. “On a good day, I can shoot in the mid- to upper 80s.”

More information about the Silva Ataxia Foundation is at silvaataxiafoundation.org.