Haiti I’m sorry

We misunderstood you

One day we’ll turn our heads

And look inside you.

—“Haiti,” David Rudder

One night in January 2010, I woke to a severe trembling in my body.

Beginning below my knees, it crept, slowly, up my legs, into my stomach, back, arms, teeth, brain. After several hours of relentless rattling, I went upstairs and, like a child, asked my brother’s wife if I could crawl into bed with them.

Eventually, the onslaught subsided, and I slept.

The next morning, my mother called to say Haiti had been devastated by a major earthquake and Port au Prince had been demolished.

I guess you could say I was too “attached.” Haiti had had its way with nearly everything I’d once thought true, and I’d accepted that it would always keep me at arm’s length, but never let me be.

When Seth Rolbein and I went there two weeks later, we found Hiroshima-like devastation. In 36 seconds, the quake had crushed neighborhoods, markets, roads, government buildings beneath the lintels of their own concrete roofs, along with everything and everyone inside. We could only imagine the sound, and the terror.

The findable dead were being trucked off to a burial pit outside the city while those spared had rigged blanket-and-rag shelters in any open space.

Driving a familiar road, we stopped to stare in horror, in tears, at what had been a rickety neighborhood of shacks constructed on the steep slopes above the harbor. It was as if some pitiless hand had smeared it off the face of the hillside the way a child might wipe out a sandcastle.

Later, some of us returned to the Haitian island of La Gonâve, where we had created an artisans’ center. The artists told us how it was to feel the ground rebel as shocks rumbled up from beneath the bay. They told how everyone slept outside in fear for weeks, how survivors flooded the island seeking refuge with relatives until there were no more places to hold them or food to feed them. No one there had died, but homes had been split and maimed.

At the school, we explained how earthquakes were caused by tectonic plates shifting, not the smiting hand of God. But neither they nor I was convinced. We assumed it was probably both.

An outpouring of heartfelt donations allowed us to help one village rebuild. But Seth and I saw the gleam in the eyes of political and business leaders anticipating a flood of international funding to “fix” Haiti — now that it had been leveled.

“How do you fix Haiti?” many have asked. Some have offered suggestions.

You don’t “fix” a country the way you fix a car. A country is not just a bucketful of humans. A country is a living, permeable organism, deeper than its official history, more than its current name, beyond its own self-concept much less the concepts of outsiders, a being entangled in the flux of living and dying. This must be remembered by those intoxicated by the urge to “fix.”

Haiti is where I experienced the electrifying difference between fear and dread.

We who return to Haiti experience many “newsworthy” moments: assassinations, coups, the oily smoke of burning barricades blackening the air. I’ve been in the mansions and the slums, brushed flies off babies, seen the bald skulls of rock jutting from razed mountainsides, shaken the hand of a torturer running for president, and witnessed a thousand men and women risking their lives to have their votes counted.

Now the news is another earthquake on Aug. 14, magnitude 7.2, that destroyed or damaged 130,000 homes. Each time violence drags Haiti into our line of vision, I yearn to turn our gaze not on an “alternate Haiti” but a subjective Haiti. “My” Haiti.

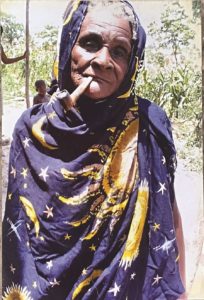

How do I explain the importance of the imperious old woman, rumored to be a werewolf, deciding that you’re friends because your first names are similar.

Of joining a family telling riddles as if for the first time, although they’ve all known the answers since childhood.

Of knowing what it’s like to have an egg, or a tin of evaporated milk, or a live chicken, slipped into your hand as a gift.

Of dancing a ferocious dance with a woman whose body had been taken over by a god.

Of witnessing the nearly inhuman endurance of drummers beating the heart and blood of Haiti into existence for nights on end.

Of stepping into a matrix of city alleys where artists fashion haunting, brutal sculpture from scraps of objects wrecked in the earthquake.

Of feeling the weight of a child’s dusty head dropping on your shoulder, as if she were suddenly safe.

Of applauding skinny boys walking on their hands for your amusement.

Of experiencing a new gratitude induced by a Coke — with ice.

Of watching a grown man see a swimming pool for the first time, then stepping in.

Of pondering the suicide of an elder, his heart broken, it’s said, by a much younger woman — or by a curse.

Of cringing as a few raindrops render unsalable a silk painter’s scarf that had taken two days to complete.

Of gazing at the Milky Way’s laden arm as it arches over a sky pulsing with haloed stars.

Of listening to workers building a house by moonlight.

There are thousands more.

The most clarifying thing I ever heard said about Haiti went something like this: Stay a week and you think you can write a book. Stay a year and you can’t write a paragraph.

Yet here I am, compelled, along with so many writers of greater insight than mine, to write. Why?

To witness. To rage. To wake up somebody, anybody, to what’s happening. To exalt. To bless. To decompress. To believe. To be able to sleep.