Kim Powers is a one-woman drug-addiction harm reduction brigade. She is waging a solitary campaign to stem the rising tide of drug overdoses and deaths on Cape Cod and the Islands by providing services, including clean syringes, to drug users right where they are, in their homes and camps — a practice that has been endorsed by health authorities but remains too controversial for public health agencies and nonprofits to take on.

“We have blanketed the Cape with Narcan, and our overdose numbers have not come down,” said Powers, 56, who was the health outreach coordinator for drug users at the AIDS Support Group of Cape Cod (ASGCC). “Why?”

The statistics bear her out. Although the state has increased funding for drug addiction by 175 percent since 2014, when Gov. Deval Patrick declared opioid addiction a public health emergency, overdose fatalities hit record levels in 2020, after a small dip in deaths.

Anyone can now get Narcan, the life-saving overdose reversal medicine, without a prescription, at any pharmacy. Still, overdose deaths were up 5 percent in Massachusetts and 30 percent nationwide last year. Preliminary figures show another 2-percent increase thus far in 2021, according to the Mass. Dept of Public Health (DPH).

Overdoses claimed two lives in Eastham, one in Provincetown, and one in Wellfleet in 2020. Ambulance crews responded to 12 opioid incidents in 2020 in Provincetown, placing the town in the second-highest per-capita category in the state (401 to 500 cases per 100,000 people). The Eastham rescue squad responded to eight opioid calls last year; Truro and Wellfleet had between one and four each, according to the DPH.

A ‘Difference of Opinion’

After 20 years of work in drug harm reduction, Powers has seen it all. She worked at Gosnold Treatment Center in Falmouth and with the Barnstable County drug court, and she owned the first sober home for women on Cape Cod for 12 years.

After six years at ASGCC, Powers was fired in January 2021 over what she described as a difference of opinion on how to do harm reduction. Dan Gates, executive director of ASGCC, said he could not comment on Powers’s discharge for legal reasons.

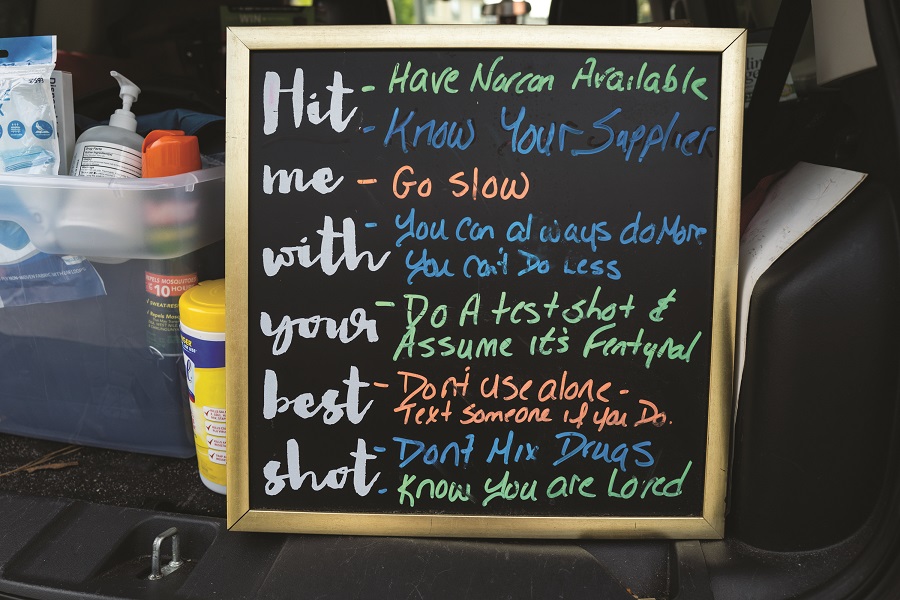

Harm reduction means helping drug users even though they are not ready to stop. It includes giving out clean needles to prevent the spread of AIDS and hepatitis C, treating wounds from injection drug use, keeping people hydrated and fed, and teaching them the safest ways to use narcotics. For example, if you have to use heroin, don’t inject it, Powers said. It can be snorted much more safely.

Without a formal organization supporting her, Powers is doing exactly what she thinks will work and was not possible in her previous position. She is driving from town to town with her SUV filled with syringes, naloxone (brand name Narcan), fentanyl test strips, and other medical supplies. She posts her phone number on Facebook and Instagram and has a weekly route: Mondays, it’s the Outer Cape; Tuesdays, the Lower Cape; Wednesdays, the Upper Cape. On Thursdays she meets the ferries in Woods Hole, and Fridays it’s Hyannis, Yarmouth, and Dennis.

Her mobile treatment approach has been adopted by many organizations as a way to reach people isolated by the pandemic and plagued by fentanyl, a powerful and deadly substance that is found in most heroin.

The ASGCC has had a needle-exchange van in Falmouth, and the federally funded Healing Community Study has paid for a mobile clinic to provide suboxone, used to treat opioid dependence, and medical care (but not needles) to drug users in Bourne and Sandwich.

Staying on the Line

Powers offers her clients more than needles and Narcan.

She asks people to call her and stay on the line when they use heroin. If there is silence for too long, she dials 911. (The users are safe from arrest under the state’s Good Samaritan Law.) In all other ways, her program allows users to remain anonymous.

If her clients are about to use drugs while she is present, she will go wait in her car.

“This morning, at a house in Forestdale, they had drugs and so I sat in my car and waited 20 minutes until someone came out and said it’s OK,” Powers said last week.

Supervised injection sites are not legal in Massachusetts, and even if they were, neighbors’ objections would be a huge obstacle. Powers said she has given out too many needles at the ASGCC in Hyannis to people who were found dead soon afterward. Once that happens to you, she said, you understand the reason for supervised injection sites.

“People are dying in their houses, especially because of Covid,” said Powers. “So, my goal is to go to where people are using. If they want MAT [medication-assisted treatment, that is, methadone or suboxone] I do that. If they are going to keep using, I try to tell them how to do it and try to keep them safe.”

Powers’s methods recall the underground needle exchange networks that supplied drug users with naloxone and clean syringes in the 1980s and 1990s, when possession of both was illegal. Underground needle exchange workers saved Powers’s life in the 1980s in Boston, she said, when she was both a heroin addict and a sex worker.

112 Outer Cape Clients

Powers’s practice is growing weekly. She said she has 31 clients or “partners” in Provincetown, 26 in Truro, 37 in Wellfleet, and 18 in Eastham. She visits both houses and homeless camps, including three camps in Truro and two in Provincetown, she said.

“Giving out these supplies — naloxone and needles — is at the core of our health policy,” said Dr. Alexander Walley, medical director of the overdose prevention program for the DPH and an addiction specialist at Boston Medical Center. (His name appears as the prescriber when you obtain naloxone at Massachusetts pharmacies.)

“If we have one overdose prevention message, it is do not use alone,” Walley said.

But using narcotics is illegal — and highly stigmatized. How do you keep it a secret and also do it with other people, Walley asked. “We will be looking at people like Kim to help us think it through” and find new ways to attack the problem, he said.

Powers’s biggest asset is establishing relationships with the users, a factor that cannot be underestimated, said Walley.

“You need to be able to engage with people and see them,” he said. “I know Kim is especially good at that.”

Powers is rich in experience, but not much else. Without a regular job, she relies on donations to pay for her supplies. Her fledgling organization, called AccessHope, has obtained corporate certification, the first step in achieving 501(c)(3) nonprofit tax status. She awaits word on a grant application to the Healing Community Study administered by Boston Medical Center. The hospital received $89 million to lead the research on various approaches. The goal is to bring overdose deaths down by 40 percent in the areas chosen for the study, said Jenny Eriksen Leary, associate director of media relations for the medical center.

Powers also hopes to get some of the $11.5-million settlement from lawsuits against companies that profited from opioids. The 21-member Opioid Recovery and Remediation Fund Advisory Council is currently deciding how to spend that money on treatment and prevention. The state expects another $90 million from a settlement with Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin.

Powers doesn’t know exactly how she can continue her program without more funding. But she knows why she wants to. In February, she said, “I had to tell a 17-year-old intravenous drug user he was HIV positive.”