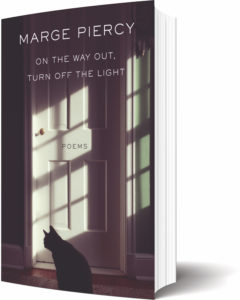

Marge Piercy’s latest poetry collection, On the Way Out, Turn Off the Light, is an ode to a life lived big and full. In these direct, earthy poems, Piercy reflects on language, Jewishness, growing old, politics, nature, loving, and leaving. The book is as rich and varied as Piercy’s own experience, with works that recall a scrappy childhood in the slums of Detroit, a dashing womanhood filled with activism and romance, and meditations of later age, with its fears and hopes for the generations to come.

Piercy is the author of 19 previous poetry collections, 17 novels, a memoir, and several nonfiction works. On the Way Out takes us into the early roots of a vocation, beginning with a section titled “Language Has Shaped My Life.”

“Words are my business,” Piercy writes, “how I’ve made house, food, machines, clothing, taxes happen every month.” Even an accomplished writer such as Piercy continues to find mystery in words, which are “pointers to fact and lies” and “go back and forth between us carrying love and promises we cherish off-key” or “jumble themselves into rich nonsense” in sleep and dreams.

Words hold the promise for Piercy of knowledge and adventure, as in the poem “Ambitious at Fourteen,” in which a glossy, gold-edged Encyclopedia Britannica holds the key to a world beyond coal furnaces and the “narrow walls” of family.

Words also give form to the shared pain of living in an unjust and murderous society. The book’s third section, “U.S.,” is an indictment of indifference, greed, and a culture of violence, where words wield power as “intent, goal, rhetoric, idioms, us versus them outside,” or distract from painful truths with numbing lies.

Piercy, long known for her political poems, writes with a voice sharpened by rage and overbrimming with human longing. These poems do not let us rest. They mourn for dying languages, for mothers “illegal with only hope,” and for children “yanked from mothers, torn from fathers by brutal strangers.” They call out the president, weapons manufacturers, the smug funders of charitable societies, and they make us look uncomfortably at ourselves. How easy it is, Piercy writes in “Call to Action,” to “turn the TV to a cartoon; go out for fast food. Bar the door. Sleep tight.”

Yet words also connect us to each other. “We have only each botched other to help us through the mud that wants to drown us, close up our eyes, shut our mouths so we can’t speak,” Piercy asserts in “I Can’t Write a Love Poem.”

This and other poems show us how to reach out of the self as a form of resistance. They remind us that we often find our humanity by facing dark nights of rage and grief. Even if the only power we can find is the ability to name “clumsy truths,” Piercy insists that we must struggle, speak, love, and share. “Something’s more than nothing,” Piercy writes. “Pick up a rock, ax, a mike, your cell, a painted sign. It’s only a short life. Spend it well.”

The poems in this collection steer us towards something larger than the self — what Piercy calls “the knowledge, the sensation of holiness.” A series of poems on Judaism recalls the horrors of pogroms, ghettos, and their legacy of trauma, as well as the witchery of ritual and prayer, the words and actions that bind families together and anchor survivors to life in all its earthy fullness.

Nature poems help us hear the “heated discussion” of crows perched outside an icy window, or translate the “chemical language” of a garden’s ripe harvest. There are poems to speak to old lovers, to praise the devoted dailiness of an enduring romance, to say goodbye, again and again, to the mother who died while the plane was still aloft. And, as the title suggests, there are poems of old age, of medicine bottles and titanium knees and the sadness of leaving behind a world still torn with poverty and war, as well as the many joys of “learning to be quiet” or lazing through late sunny mornings with a longtime lover or curling up with a beloved cat.

Piercy lives in Wellfleet with her husband, Ira Wood, the writer and radio commentator, and an extended feline family. A sought-after teacher and workshop leader, she is the judge of the annual Joe Gouveia Outermost Poetry Contest, now in its eighth year. The deadline for both the regional and national categories is Jan. 12, 2021. Details can be found at womr.org.